The archives of the Rochester Bridge Trust stretch back more than 600 years, documenting the history of the charity, recording the engineering behind the construction and maintenance of its bridges and offering a colourful record of land management through the ages. Included within the files are royal seals and decrees, remarkably detailed hand-drawn plans, account rolls and receipts, and all manner of items that bring the Trust’s history to life.

Every one of those items contributes to our understanding of the Trust and its evolution, as well as providing centuries of civil engineering records from before the term ‘civil engineering’ had even been invented.

What many people don’t realise, is that each document can also open our eyes to a wealth of secondary information, that can at times be more valuable than you would initially realise.

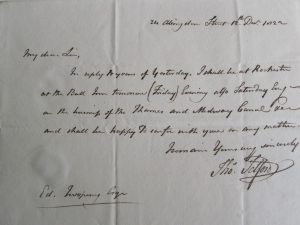

This archive is a simple note from Thomas Telford. For those who are unaware, Telford was a famous, incredibly versatile civil engineer. Known as the Colossus of Roads, he’s most well-known for the Menai Suspension Bridge but worked on countless other projects, as well as being the first President of the Institution of Civil Engineers. Significantly for us, he was also Bridge Engineer to the Trust from 1821-27.

So what makes this simple note dated 12th December 1822 so special? It’s hardly filled with text and doesn’t even mention our bridges, so why has Archives & Records Manager Alison Cable picked out this document to share?

Re-read the text and you’ll realise it’s actually crammed with interesting details just waiting to be unpicked.

Working our way down the document, the address and date line tell us where Telford was on a particular day (at home in Westminster), and where he will be the following day.

Next we find out the calibre of customer to visit The Bull Hotel on Rochester High Street in the early 1800s.

From other archives we know this letter is written at a time when Telford was engaged in the construction of a wharf at the Strood end of the medieval Rochester Bridge, and so this letter serves as a reminder that he was involved in several projects at a time – such as the Thames and Medway Canal.

Finally, we note the recipient of the letter, Edward Twopenny, the then Bridge Clerk to the Rochester Bridge Trust.

All of these components in a simple document, plan or photograph can lead a researcher off on other tangents, possibly to historical records held in other archives and libraries.

As Alison explains: “The joy of being an archivist is knowing that a document forms part of a network of archives collections that help the researcher to build a picture of what happened where and when – and hopefully why.”

Looking back through this note and seeing the possible opportunities to be investigated, just imagine how many leads a longer, more detailed letter might offer.