The Life and Works of John Rennie (7 June 1761 – 4 October 1821)

Portpatrick Harbour

William Allsop

At a distance of only 21 miles from Ireland, the port of Portpatrick on the west coast of Scotland had been hosting irregular ferry services to Donaghadee since at least the early 1600s, probably from a sandy pocket beach between rock headlands. Weekly post services were established by the Edinburgh Postmaster in 1662, increasing to twice-weekly in 1677. In 1774, the Post Office commissioned a pier or breakwater designed by John Smeaton on the south side of the harbour, followed by a lighthouse in 1790.

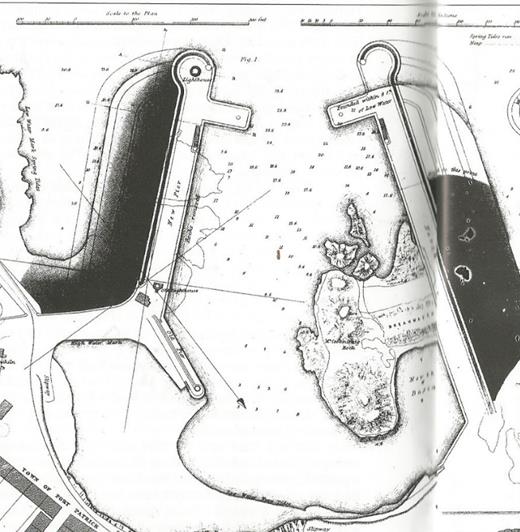

In 1802, Thomas Telford advised on potential improvements and subsequently John Rennie was appointed to make detailed surveys by between 1814 and 1818, and to design an extended harbour with two piers (Fig. 1). These subsumed Smeaton’s south harbour with new North and South Breakwaters forming two basins.

After John Rennie’s death in October 1821, the new extended South Pier and lighthouse were complete in 1836, but damage to the outer end in the Night of the Big Wind of January 1839 indicated problems to follow. Work to repair the South Pier diverted resources from the North Pier, halting the further expansion. Operation of the ferry service was moved from the Post Office, with the mail contract transferring to Glasgow – Belfast cutting this important trade from Portpatrick. It was reinstated in 1859, the new railway from Dumfries and Carlisle opened in 1861, and the new dock for mail steamers was completed in 1865. But it was all down-hill. The postal traffic moved to Stranraer to Larne in 1862, and the daily ferry service to Donaghadee ended in 1868.

The formal signifier of defeat was the dismantling of the lighthouse in 1871, being re-erected in Columbo (Sri Lanka), and the formal repeal of the harbour acts for the port soon thereafter.

Whilst Rennie’s South Pier had been completed in 1836 by his son, Sir John Rennie, albeit then damaged, it does not appear that the North Pier was ever completed to its intended length. Over time, the blockwork walls, and intermediate fill of both breakwaters have been washed away by wave action, and the arisings now appear as informal mounds around the surviving ends of those original walls, traces of which can be seen in Figs. 2 and 3.