The Life and Works of John Rennie (7 June 1761 – 4 October 1821)

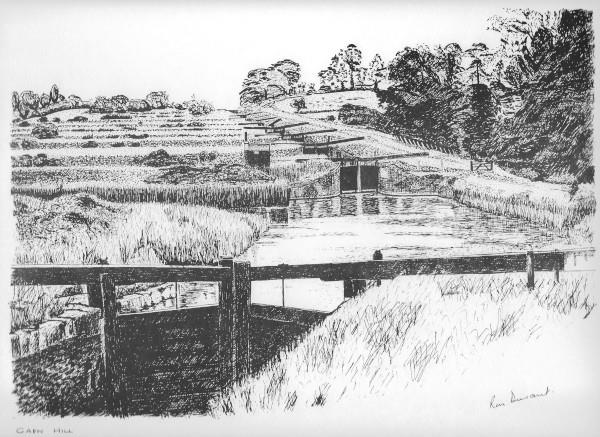

Kennet & Avon Canal - Caen Hill Locks

David Newman

The spectacular descent of the Caen Hill flight of locks in Devizes is one of the most impressive sights along the Kennet and Avon (K&A) Canal system. Caen Hill is of particular interest due to its status as a scheduled ancient monument and its position as one of the top three tourist attractions in Wiltshire.

Just to the west of Devizes the canal changes level rapidly as it drops 237 feet in two miles through 29 locks to the Avon Valley. The most spectacular of those locks are the 16 which descend Caen Hill in one straight flight. The steep descent of the closely-packed locks and use of side-ponds creates an unusual and beautiful sight, not to mention a haven for plant and wildlife, attracting thousands of canal users and visitors every year. The locks are so close together that each pound has had to be extended sideways to give a reserve of water for lock operation.

As far back as 1788 a ‘Western Canal’ was proposed to improve trade and communication links to towns such as Hungerford and Marlborough. The following year the engineers Barns, Simcock and Weston submitted a proposed route for this canal, although there were doubts about the adequacy of the water supply.

John Rennie found that there was in fact insufficient water available on the original Marlborough route and recommended that the canal should be built via Devizes. It is likely however that it was not only the lack of water that prompted this decision, the new route was in fact agreed as a result of lobbying by two Devizes MPs. In 1793 a further survey was conducted by John Rennie, and the route of the canal was altered to take a more southerly course through Devizes, Trowbridge and Newbury. The proposed route was accepted by the then ‘Kennet and Avon Canal Company’, chaired by Charles Dundas. Whilst Devizes gained economically from this decision, Marlborough did not, and as plans for a branch canal to Marlborough had also fallen through, the people of that town felt very hard done by.

They were ultimately placated however by an offer of reduced carriage tolls for goods dispatched to Marlborough.

It was John Rennie’s idea to climb the very steep Caen Hill, the last part of the 87-mile route of the Kennet and Avon Canal to be completed.

While the locks were under construction a horse drawn tramway provided a link between the canal at Foxhangers to Devizes. Its remains can still be seen in the towpath arches of all four bridges crossing the Devizes Flight over the canal.

It is November 20th, 1803, and John Rennie wrote: “There is good clay for bricks west of Scots House and there is an abundance on the face of Devizes Hill. I think 3½ or 4 million may be made at these places in the course of the ensuing season.”

John Rennie’s navvies dug a brickyard to the south of the workings on the hillside between the towpath and the main road. Bricks for the Caen Hill Flight lock chambers were made from local gault clay. Two million bricks per year were supplied for the canal.

It is March 22nd, 1803, and following an inspection of the tramway, John Rennie commented: “The tramway in general is badly formed and the rails are badly laid. The sleepers are of wood but are too narrow. The waggons are badly formed and are so large and clumsy that they are a load for a horse themselves”.

When the flight of locks opened in 1810 barges were able to navigate the entire canal. The ‘toll’ per ton from London to Bath was £2 9s 6d, far cheaper than carriage by road. By 1818, seventy 60-ton barges were working on the canal, mostly carrying coal and stone. The journey from Bath to Newbury took an average of three and a half days. So, the canal was not only cheaper, but faster than road, vindicating Rennie’s recommendation to adopt the more challenging but more direct route.

For thirty years traffic on the canal grew and grew, with annual receipts between 1824 and 1839 in excess of £42,000 with a dividend of 3%.

The Decline of the Canal

As soon as the Great Western Railway (GWR) started operating from London to Bristol in 1841, the competition started affecting canal trade. Ironically much of the canal company’s profit in the late 1830’s came from transporting those self-same materials that were used to build the railway.

For the next ten years the canal company fought back against railway competition by reducing tolls and introducing its own fleet of barges.

Later, as matters got worse, there were staff cuts and wage reductions and canal traders increasingly turned to the railway, viewing it as a more economical means of transporting their goods.

Railway Take-over and Operation

In 1852, the GWR obtained Parliamentary approval to take over the whole canal. The canal company shareholders were guaranteed an annual payment and the GWR promised to keep the canal in good repair and try to run it in a business-like way. However as profits gradually disappeared, they too began to cut staff and reduce repairs.

Lack of maintenance

During the years 1945 to 1948, the canal suffered even further decline due to a lack of maintenance and use although a number of smaller traders still used the waterway.

New management

As a consequence of railway nationalisation in 1948, the canal, including the Caen Hill Locks, came under the management of the Railway Executive and later under the Docks and Inland Waterways Executive. For a short while there was an upsurge in canal trading, when a number of enterprising businesses found cargoes to carry.

Closure

However, from the early 1950’s the DIWE effected a number of closures for repairs, and this made trading more and more difficult. These repairs were never satisfactorily carried out, and in 1955 the Transport Commission went to Parliament to close the canal.

Restoration and Upgrading of Caen Hill Lock Flight

A few years later and after considerable campaigning, the restoration of the Kennet and Avon Canal was started and the Kennet and Avon Canal Trust formed. After several decades of fundraising and hard work, the canal was re-opened by Her Majesty the Queen in August 1990.

A Back-Pumping Station opened in 1996. The pump house, built in character with the canal architecture is situated just below bridge 146 and down from Lock 22. As the name implies water is pumped back to the top of the flight by two 250kw pumps, with a maximum output of 32 million litres per day, the equivalent of one lockful every 11 minutes. The pumps are electrically driven and powered in part by 208 solar panels installed in 2012 at Foxhangers.

John Rennie’s Caen Hill, is now a very special place. After more than four decades of restoration, the canal is once again open for business, albeit business of a very different kind from John Rennie’s industrial origins. Pleasure boating, fishing, walking and cycling, the canal has something for everyone.